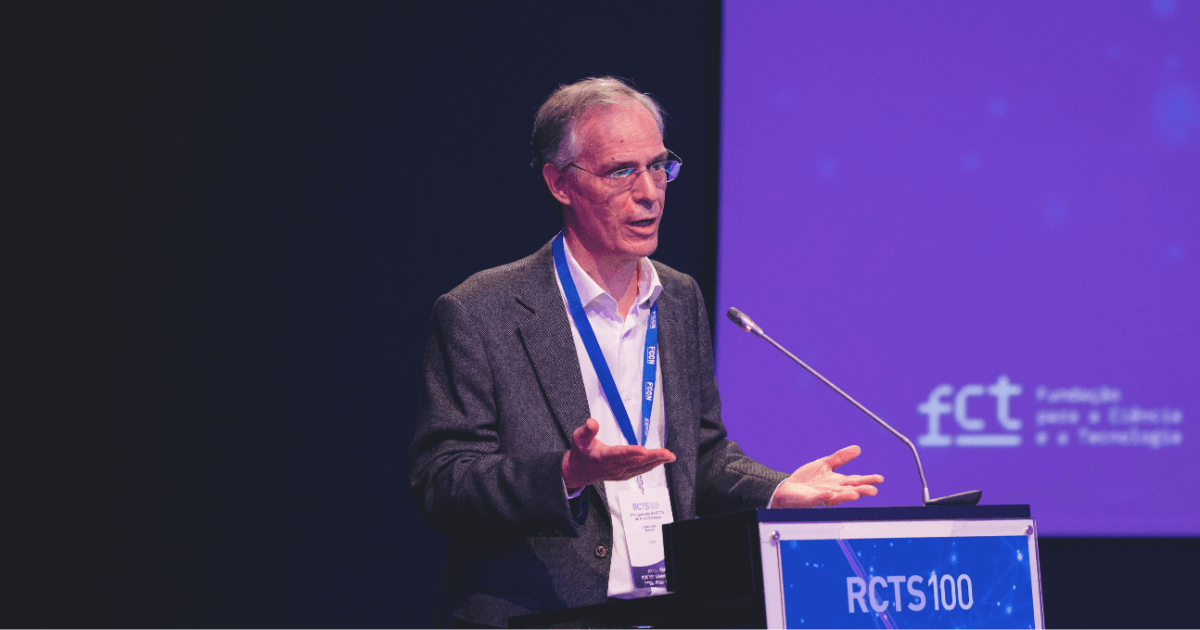

The computer scientist Fernando Boavida He was one of the members of the team that, in 1991, connected Portugal to the Internet. Thirty years later, the University of Coimbra professor and researcher describes the work carried out and the environment experienced by those who carried out this pioneering work. He reflects on the transformations that occurred over the following three decades: "The Internet has radically changed society."

This fall marks 30 years since Portugal was connected to the Internet. Can you describe the role of the FCCN Unit (then Foundation for the Development of National Means of Scientific Calculation) in this process?

The Foundation for the Development of National Scientific Calculation Methods played a key role in connecting Portugal to the Internet, by supporting a project proposal submitted to the Science Program, which ultimately provided the resources necessary for this connection. The project was the result of an initiative by university professors and researchers, informally led by Professor Doctor José Legatheaux Martins, which was, from the very beginning, the "soul" of the entire process. The Foundation, represented by Professor Vasco Freitas, was always fully committed, immediately recognizing the importance that internet connectivity would have on the national scientific and academic community and the resulting potential for the country's development and modernization.

As a member of the team that implemented the project to connect Portugal to the Internet, what can you tell us about that time and that experience?

These were times of great enthusiasm and sincere collaboration between universities, as well as between them and the FCCN. Commercial communication services available at the time were quite limited and expensive, so the possibility of having more effective means of communicating with the international scientific and academic community was something we all yearned for. This enthusiasm extended to each participating institution.

In the case of the University of Coimbra, the Communication Networks group, led by myself and my colleague Edmundo Monteiro, was directly involved in the process. In fact, initially, the access point for the entire University of Coimbra to the then-designated National Scientific Calculation Network was supported by a single server from the Communication Networks group, the mercurio.uc.pt machine. Later, during the "production" phase, which was generalized throughout the University of Coimbra, this access was provided by the University of Coimbra Informatics Center (CIUC), whose technical director was Eng. Mário Bernardes.

Over the next three decades, we witnessed an exponential evolution of the Internet and underlying technologies. Was this something you anticipated as the path forward in the early 1990s? Was its impact on society predictable?

Computing, networks, and computers are so ubiquitous in every aspect of our lives that we hardly notice them anymore. Our reality confirms the vision of Mark Weiser, the computer scientist who, in the distant 1980s, devised and defined the concept of ubiquitous computing, according to which technologies would be so present in our lives that they would be nearly invisible. Despite this vision, more focused on computing than communication, the Internet's impact on society has surpassed anything imaginable at the time. This, after all, is the most exciting part of scientific and technological development, which consists of small steps that, unexpectedly, can lead us to discover completely unexpected "landscapes."

The Internet has radically changed society. It began by transforming the scientific community, then drastically changed the business of telecommunications operators—which, in just a few years, saw the disappearance of business models that had existed for decades—and suddenly made enormous volumes of information available to the general population. After that—and based on it—e-commerce, all kinds of online services, teleworking, social networks, cellular networks, communication between all kinds of devices, interaction between the virtual world and physical devices, and smart buildings, cities, and transportation all developed.

Today, very little can be done without Internet access, and everything runs on IP technology, to the point that elections, wars, attacks, and crimes are also based on the Internet. Not even Mark Weiser could have imagined all of this in 1990.

Do you feel that the online world today fits, globally, with the objectives and mission that were advocated in 1991?

No one can want to condition technological evolution to objectives or missions established three decades ago. When an idea is disseminated or a challenge is launched, we realize we've contributed a starting point, but the decision about the path to follow lies in the hands of those who build it. Naturally, we can and should influence evolution to the extent possible and desirable, just like any other stakeholder.

Internet technologies and the highly distributed environment in which we live have recently enabled the development of applications for monitoring people and extracting knowledge, for a wide variety of purposes. The real world is increasingly becoming an artificial world. We are moving toward a society we don't want, one that is too artificial, in which everything is entirely predictable and controlled.

Deep down, we don't want the homes we live in to control us or tell us what to do. We don't want to be constantly located—at school, at work, or at leisure. We don't want to be told which way to go from A to B because, sometimes, it's when we get lost that we find ourselves. We don't want some intelligent system constantly measuring our vital signs because that's not what gives us the joy of life. Perhaps Artificial Intelligence and the so-called Internet of Things can bring many benefits, but the truth is that we, human beings, don't want to be the Things of the Internet.